Scaling Pathways

Scaling a venture is a bumpy ride, with highly unpredictable factors.

These ventures operate, and grow, against a web of uncertainty and complexity. As a result, successful scaling often rests on a combination of strong leadership and managerial skills, creativity, organisational agility, calculated risk-taking and luck.

We have considered four African entrepreneurship ecosystem contextual factors vis-à-vis a global scaling lens:

The scale-up animal menagerie to describe growth strategies for Africa, given the elusiveness of the metaphorical unicorn in African habitats.

Scaling archetypes through an innovation perspective.

The universal(ish) phases of scale, whereby specific interpretations might be more nuanced.

Minimum operational requirements for African scale-ups.

The scale-up animal menagerie

Unicorns

The unicorn model of seeking to achieve a $1 billion valuation in the shortest time possible is highly contingent on mature capital markets and sophisticated intermediaries who can broker investment deals large enough to boost growth without revenue. This rapid, organic, winner-takes-all scaling strategy - immortalised as ‘blitzscaling’ by LinkedIn Founder Reid Hoffman - has proved to be nearly impossible to achieve in the complex African context to date.

“There aren’t rules governing organisational growth when you’re blitzscaling; you use heuristics instead—and by that I mean guidelines that help you make decisions and learn on the fly. Blitzscaling is always managerially inefficient—and it burns through a lot of capital quickly. But you have to be willing to take on these inefficiencies in order to scale up. That’s the opposite of what large organisations optimise for.” - Reid Hoffman

Fast (or blitz) scaling entails rapid growth, leveraging strong network effects to attain market share. Prof. Tim Weiss notes that blitzscaling is often cast as decontextualised and a poor fit for Africa.

The Nigerian health-tech venture 54gene, Nigerian fintech ventures Paystack and Flutterwave, and the Tanzanian fintech startup Nala are a few of the companies pursuing blitzscaling strategies. At the time of writing - and depending on the definition applied - there are (or have been) at least 7 sub-Saharan African unicorns: Andela, Interswitch, OPay, Wave, Jumia, Flutterwave and Chipper Cash. These unicorns are predominantly Nigerian and fintech-oriented. (Whilst Go1 and Konga are sometimes identified as unicorns, Go1 is an Australian company - with a South African co-founder - and we are unable to find sufficient validation of a $1bn valuation of Konga.)

Gazelles

‘Gazelle’ is a term coined by American economist David Birch and refers to ventures that exhibit at least 20 percent revenue growth year on year for three to four years. Such ventures solve real problems and are born out of ecosystems with harsh conditions, external shocks and fewer resources. As a result, they spend less cash as they grow, ultimately reaching profitability sooner, surviving longer, and producing compelling returns. Importantly in the African context, gazelles are also outstanding job creators.

“In Africa we need gazelles, not unicorns.” - interviewee

“[A] Unicorn is a mythical creature. Very un-African. But in Africa, we have the Gazelles. The African Gazelle is a sleek and stable creature used to the tough turf of Africa. So, the conversation has been raging. Should we follow the rest of the world led by America to continue looking for our own Unicorns or to define our Gazelles and look for them across Africa?”

In Africa, a gazelle is generally understood to be valued at $100 million or more, and generates revenues of $15 to $50 million. South African fintech venture Jumo and Kenyan energy venture M-KOPA are notable examples. Mature and growing gazelles are often referred to as ‘soonicorns’.

Camels

Author Alex Lazarow uses a camel analogy, which he uses to explain how firms can survive through crisis, and sustain and grow in adverse conditions. Camels do this with various strategies:

They execute balanced growth rather than blitzscaling-style burn;

They take a long-term outlook not dictated by fund cycles;

They weave diversification into the business model; and

They seek growth through organic revenue, with limited external investments.

In a Harvard Business Review article, and later via his book, Out-Innovate, Lazarow notes how camels are built for the long haul, that breakthroughs don’t come immediately, but rather occur later in the company timeline. Survival is often the primary strategy. This allows time to build the business model, find a product that resonates with the market, and develop an operation that can scale. The race is about who will survive the longest, not about who goes to market first.

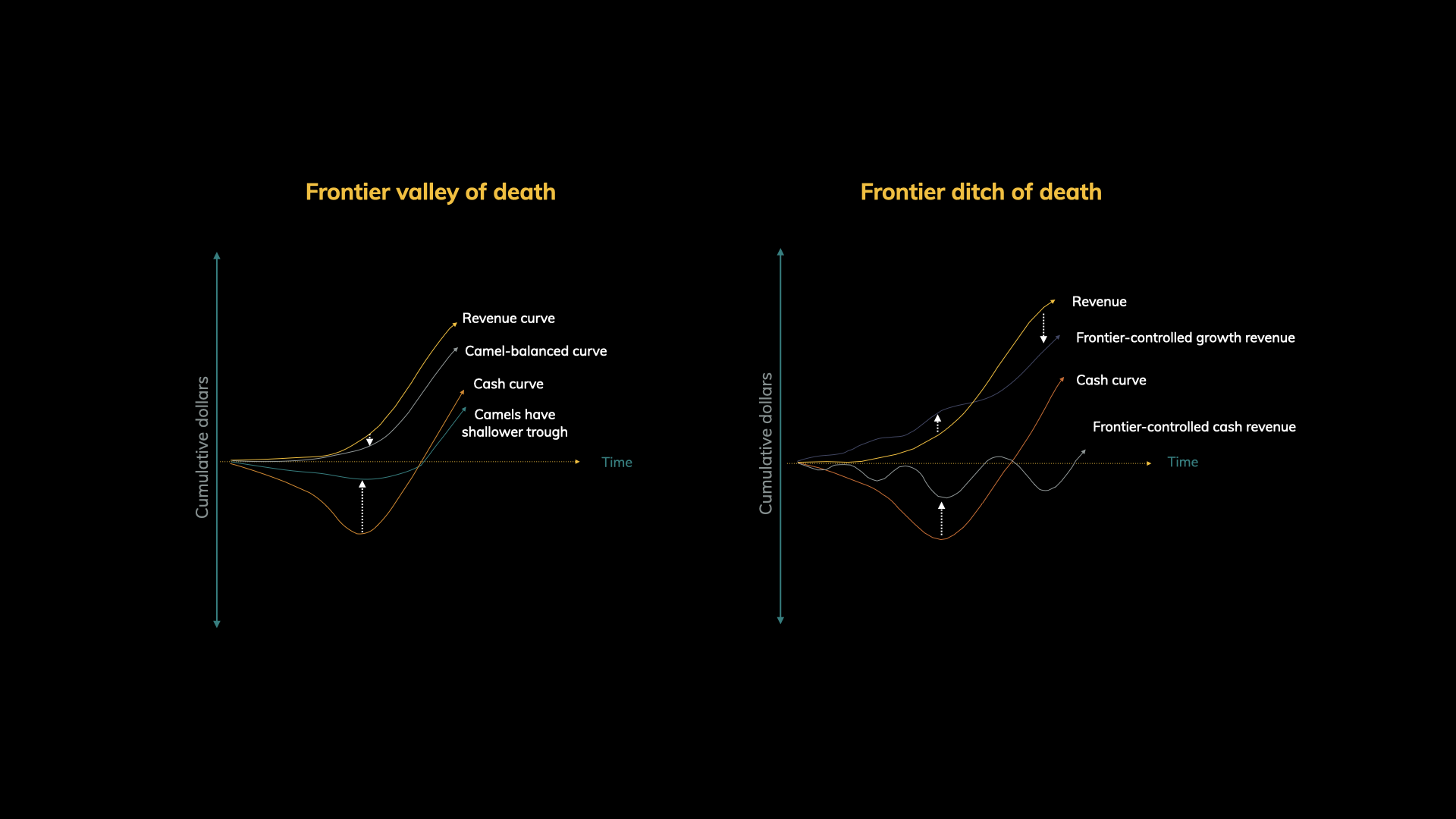

Cash curves do not dip as deeply (compared to Silicon Valley firms), as indicated by Figure 11. With balanced growth strategies, firms can grow in controlled spurts, choosing to accelerate and invest in growth (thus accelerating revenue and cash spend) when the opportunity calls for it. Growth is pursued in manageable increments, instead of a single, large, unsurpassable valley of death.

Figure 11: Cash curve comparisons Source: Out-Innovate

By prioritising balanced growth, building for the long-term, as well as deepening and diversifying for resilience, camels can not only survive market shocks, but can also grow and thrive in good times and bad. In short, they turn adversity into an advantage. This growth model does not depend on an exponential curve of user adoption, and instead focuses on gradually converting users to paying customers and increasing profitability. African examples include Ghana’s e-commerce venture Hubtel, Kenyan logistics venture I-procure, and Nigerian fintech Interswitch (now a unicorn, but it took nearly 20 years to get there).

Zebras

The new wildlife-on-the-block, zebras have an impact stripe. These are profitable businesses that solve real, meaningful problems and in the process repair existing social systems. Zebra founders’ personal connections to their companies means they strive for capital efficiency, and tend to avoid trading equity for venture funding. Zebras also build cooperative relationships with other startups.

Whilst the zebra concept - which has spawned a cooperative movement in some developed markets - has not yet taken off in Africa, we anticipate that its principles will align with established social entrepreneurship models.

Scaling archetypes through an innovation lens

Successful scaling, especially in Africa, has numerous layers of complexity, especially the interplay between scaling up and scaling out (or wide) to obtain growth.

“There are huge opportunities for scaling wide on the continent, rather than scaling up as such. There are different levels of technology, and many opportunities for micro-businesses using low-tech approaches to service needs for the wider population that are not high end products. The technology entrepreneurs on the continent are not fully awakened to this. They are not focused on the need to scale wide, and actually meet the needs of the local population. This is partly because many of these tech entrepreneurs have been supported by organisations from Western countries, and are working on the basis of the paradigm of what is happening in the UK and the US. But the African market is different, and I think technology entrepreneurs need to be alive to that, and scale up differently - or scale wide - and then they can then build the market, transform it gradually, and create real value for the populace.” - interviewee

When devising a scaling pathway, academics from the consortium OpenAIR have usefully considered the following scaling archetypes:

Scaling by expanding coverage. This can include geographical expansion and reaching new consumer segments.

Scaling by broadening activities. This might involve adapting product innovations, engaging in process or organisational strategy innovation, and increasing scope of activities.

Scaling by changing behaviour. This might involve deeper collaboration with the ecosystem and stakeholders, and building partnerships to expand reach.

Scaling by building sustainability. Here, increasing capacity and developing human capital and engaging in open collaborative innovation are key.

It is acknowledged these frames were designed for social entrepreneurship contexts but it is likely there is some applicability to commercial scaling realities.

The Scaling Journey

Scaling has been described as an art, which is helped by combining skill alongside serendipitous timing with good luck. How contextual factors (art) interplay with scaling principles (science) matters. Innovation - the process of continuous experimentation and iteration: assessing what works, and learning from mistakes using black-box thinking - the willingness and tenacity to investigate the lessons that often exist when we fail - is a consistent driver.

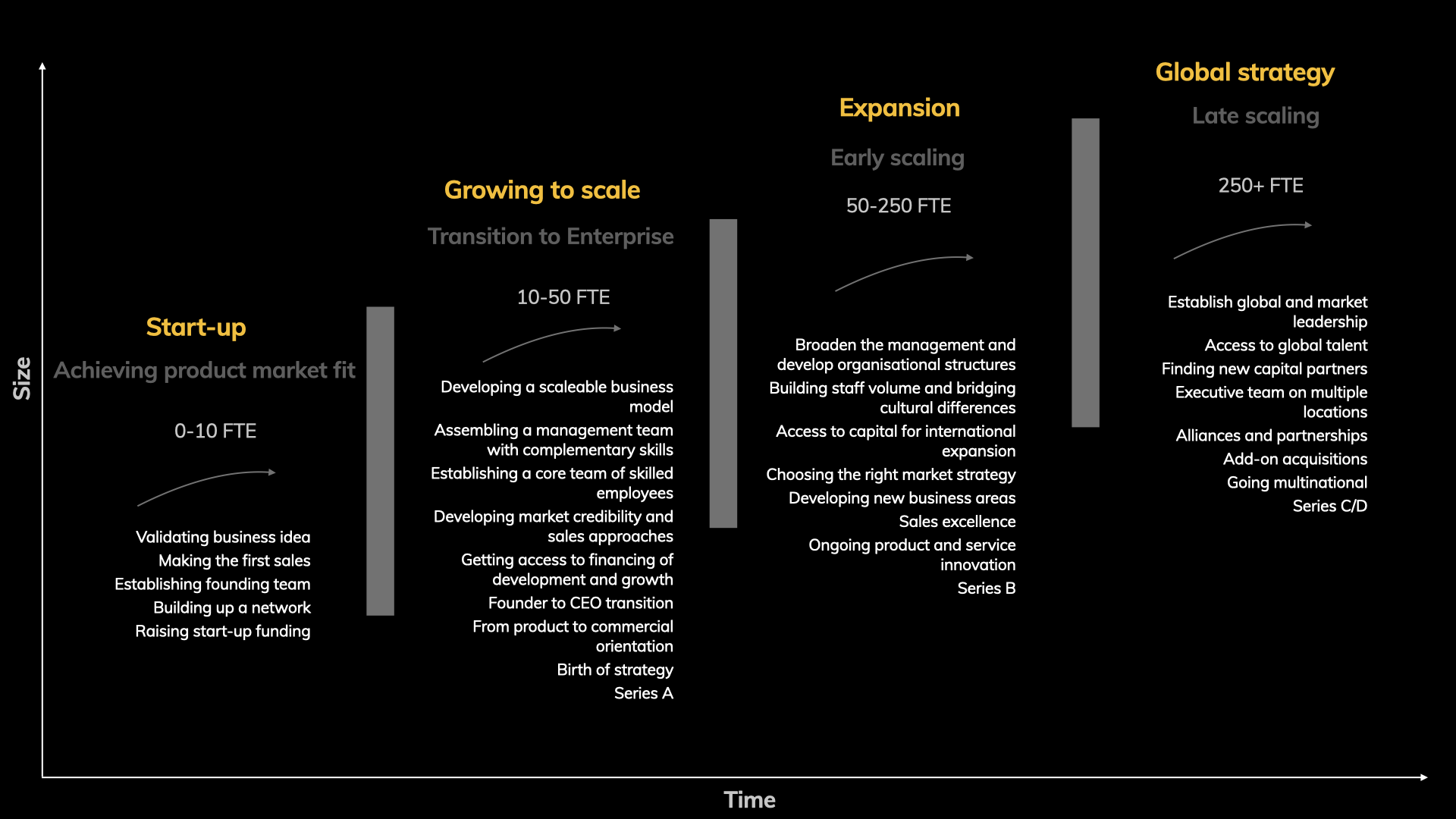

There are notable and somewhat distinct phases in the scaling journey, some of which are generally universal, as indicated by Figure 12, as informed by Nordic Scalers.

Figure 12: The Scaling Journey Source: Nordic Scalers, Nordic Cooperation

Phase 1 - Startup (pre-scale)

As articulated by leading global VC investor Marc Andreessen, being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market (i.e. product-market fit), is the only thing that matters in this phase.

It is broadly recognised that during these infancy years founders are entrepreneurially oriented, absorbed entirely by making and selling a new product. Structures and processes are highly likely to be loose, with decisions made fast. Communication among employees will be frequent and informal because the team is small.

Whilst we have not focussed on startups in our research, we acknowledge that actions taken and decisions made during this phase have direct consequences for the scaling phases.

Phase 2 - Growing to scale

It is often at this nascent stage that successful high-growth companies build the foundation for a successful growth trajectory. Key challenges include the development of a scalable business model, the creation of efficient sales channels, and the setting up of efficient organisational structures that will allow the company to grow. In a Harvard Business Review article, and then in a book, Linkedin Founder Reid Hoffman describes the scale-up phase as being when “the company develops from a family to a tribe."

Funding too is critical. As one interviewee told us, funding “infuses resilience and being able to drive the vision and the executive needs, while also being in a position to have a shock absorber when there are external or internal factors leading to challenges that shake the foundation of the business”. Until the last few years, there was very limited funding on the continent.

The angel investment network has been nascent but is fast developing with the support of organisations such as ABAN.

Business bank loans are notoriously difficult to obtain in Africa.

When VC funding is available, about half is being directed towards only one sector - fintech.

Access to public grants, and partnerships with patient lenders of private risk capital, are typically highly limited.

Debt funding and other alternative financing models are emergent but relatively embryonic.

This phase requires building a leadership team with the appropriate skills and experience to drive the venture forward on its scaling trajectory. Whilst African populations are growing, this has not been matched in human capital upskilling. There is a dearth of experienced managerial talent willing to leave their gilded corporate cages to work in scale-ups in Africa.

Generally, ventures acquire Series A funding during this phase. A checklist provided by Founders Factory Africa and Briter Bridges - Figure 13 - has helpfully distinguished key factors between pre-seed, seed, Series A and Series B phases.

Figure 13: Startup Growth Checklist. Source: Founders Factory Africa, Briter Bridges

Phase 3 - Expansion

In the expansion stage, ventures are looking to further exploit growth opportunities, and revision of business models is often needed. Scaling up can, for example, be reliant on the penetration of new international markets or the deployment of the company’s core competencies in new industries or sectors.

But as the venture grows, more complex distribution requirements require knowledge of logistical efficiencies and agent networks. Increased numbers of employees cannot be managed exclusively through informal communication. Additional capital must be secured, and new accounting procedures are needed for financial controls.

Those who excel as leaders in the growing to scale stage and the expansion stage are rarely one and the same profile. Those founders who seek to retain control over all aspects of their business may run into trouble as complexity increases. It is therefore important to establish a management team that encompasses the broader skills and experience required to help expand the organisation. The same talent scarcity and quality issues described for Phase 2 (growing to scale) apply here: talent with the required skills and experience being both scarce and expensive.

In Africa, because domestic addressable markets are limited, ventures are often required to internationalise much earlier than is the norm in developed markets (or in emerging markets with significant cumulative consumer purchasing power due to their massive populations, like China, India and Brazil). Expansion is often seen as a necessity, but it comes with additional costs and very specific challenges. The net result is that scaling is invariably more difficult.

Generally, ventures acquire Series B funding during this phase.

Phase 4 - Global strategy

The global strategy stage is when the company builds an established international presence and develops a truly global business model. Key tasks at this point include the development of global supply chains, the construction of global sales channels, the attraction of global talent, and the successful accessing of worldwide distribution networks.

Typically, the growth stages described here are increasingly capital intensive. In many cases, the level of funding needed in the later stages is ten or more times that of the funding needed in the earlier ones. This means that successful navigation through all of the stages often requires significant changes in the ownership and capital structuring of the company as it develops and progresses.

An aspect of this phase is building strategic partnerships and alliances. This is an area in which African entrepreneurship is under-developed, especially as regards partnerships with corporates and government.

Large, established corporates already have the means and assets needed to overcome the region’s structural challenges. They have access to capital, the expertise needed to navigate complex regulatory environments, and often a presence in multiple markets. African tech innovators will have a greater chance of success if they collaborate with those larger entities by providing innovative business-to-business solutions. Convincing corporates to innovate and integrate scale-ups into their ecosystems is the hard part.

Governments have an important role to play in improving Africa’s entrepreneurship ecosystem and making it easier for new companies to scale through partnerships and alliances with large companies by, for example, providing tax incentives. Governments can also help mitigate the risks arising from collaborations between scale-ups and powerful incumbents by enacting clear and strong protections of intellectual property and data, and cracking down on corruption and anti-competitive practices. Moreover, governments can bring trade laws in line with new business models and clarify current ambiguity over how they allocate responsibilities and liability between scale-ups and established corporations.

Given the nascency of the ecosystem, very few African scale-ups have (yet) achieved the level of maturity described in this global strategy phase, especially as regards internationalisation outside of Africa (where there is very limited real evidence of success).

Financial benchmarks are elusive financial data points. Private companies lack reporting requirements that would make their benchmarks known, and backers of private companies hold their portfolio company information close to the chest. Key metrics - such as annual recurring revenue (ARR), customer lifetime value (CLV/ CLTV), recurring revenue vs total revenue, gross profit, total contract value (TCV) vs annual contract value (ACV), compounded monthly growth rate, churn, investment in R&D - are essential evaluation points to determine the health (and potential) of a scaling venture.

Generally, ventures acquire Series C and D funding during this phase. Historically, African startups tend not to survive beyond Series B funding. There have been very few larger rounds. Comparatively, African ventures have lower investor returns after 5 years, as indicated by Figure 14.

Figure 14: Average return for investor after five years Source: BCG

Minimum operational requirements for African scale-ups

As a minimum, scaling ventures in Africa should aspire to bedding down the following aspects of good governance and operations:

A highly investible leadership team with credibility and capability;

Strong corporate governance and risk management and mitigation strategy;

Strong and diverse board composition (including gender diversity);

Succession planning (leadership team, senior management, board);

Adherence to regulatory codes and self-regulatory policies;

Strong financial modelling alongside growth forecasts; and

Audited financial statements on an annual basis.

Over time, as a venture matures and reaches the global expansion phase, incorporation of additional operational measures, such as those listed below, is likely to increase investor confidence:

Corporate citizenship, social impact and sustainability policies, plans and programmes;

Adoption of and compliance with know-your-customer (KYC) standards & integrity policies (including anti-money laundering measures);

Full statutory and regulatory compliance, with strong legal counsel;

Adequate safeguarding of intellectual property rights through patent and related IP applications, as appropriate;

Security policies and systems;

Appropriate insurance coverage (covering assets, staffs, contract workers, indemnities, business continuity, security, unforeseen activities); and

Quality certifications (e.g. ISO 9000), as appropriate, and ongoing compliance with relevant quality management standards.